Choose the Right Chatbot for User Trust and Engagement in High Privacy Sectors: Education, Health, Legal and Government

- Rikki Archibald

- Mar 2

- 24 min read

Updated: Mar 3

*This article is a truncated version of my Master’s thesis, which I completed in late 2024 as part of my Master of Business Administration in Leadership and Strategy with the College of Paris through Ducere Global Business School.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

As organisations in high privacy sectors, such as education, health, legal, and government, look to improve customer service outcomes, the implementation of rule based “Basic Chatbots” and more complex artificial intelligence powered ”AI Chatbots” has arisen as a promising solution. However, the successful integration of chatbots in these sectors turns on several critical factors. These include ensuring data privacy and security, designing user friendly interfaces that nurture user engagement, and providing accurate and reliable responses that meet the unique needs of these sensitive environments.

Despite the potential benefits, many organisations struggle with effectively deploying the right chatbot in a way that maximises user satisfaction.

This research identified two critical pathways that organisations must choose between when implementing chatbots to ensure high user engagement and security. Using a mixed method approach to the research, initially a review of the existing literature was completed on the topics of data security and anthropomorphism (or “humanness”) in the design of chatbots. Secondly a survey was undertaken eliciting both quantitative and qualitative feedback on user experience covering chatbot functionality, feeling and data security and privacy.

The key findings are that anthropomorphism does not currently have a significant impact on user engagement, whereas reliable functionality is much more significant. When deploying chatbots, organisations need to be very clear on the purpose, and whether the type of chatbot chosen will be able to effectively achieve that purpose and thereby deliver user satisfaction.

Ensuring the correct type of chatbot design can assist organisations to avoid unnecessarily engaging the data collection and privacy requirements under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Official Journal of the European Union, 2016) which also benefits users who are reluctant to provide unnecessary personal data. When deploying AI chatbots, it is recommended that organisations consider liability if the incorrect answer is given by an AI Chatbot and implement more robust security features to protect user data.

1. Table of Contents

2 Introduction - Choosing the Right Chatbot

2. Introduction - Choosing the Right Chatbot

Technology and particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI) is changing the way we do business and having a significant impact on the methods used to provide better customer service. One rapidly growing use of AI which has become particularly popular within customer service is chatbots, also known as virtual assistance or service bots (Lappeman et al., 2023). These are computer programs that simulate humanlike conversation with an internal or external customer.

Not all chatbots use AI, some are rule based and simply generate support tickets for the customer service team to action, or they direct customers to knowledge base articles (Basic Chatbots) (IBM, 2024). However, the next generation of chatbots offer enhanced functionality which allows them to understand common language through AI techniques such as natural language processing (NLP) as well as allowing them to adapt to a user’s style of conversation, identify and retrieve relevant information from previous conversations, and simulate empathy when answering questions (AI Chatbots) (IBM, 2024). This personalisation of service usually requires users to disclose more personal information and has given rise to privacy concerns (Lappeman et al., 2023; citing Widener & Lim, 2020).

While chatbots offer significant potential for improving customer service efficiency and accessibility, their success largely depends on user acceptance and satisfaction.

This research investigates the key considerations when implementing customer service chatbots in high privacy sectors such as higher education, health, legal, and government. It identifies a set of criteria which organisations can apply to determine which type of chatbot, a Basic Chatbot or an AI Chatbot, best suits the customer service scenario and to identify the best strategies for designing and implementing chatbots that encourage user engagement in privacy-sensitive environments.

There is a significant need within these sectors to ‘keep up’ with technological developments as these industries are growing rapidly and often struggle to deliver high quality customer service on limited budgets. To function, these industries require consumer trust and have a responsibility to handle sensitive personal data, such as health information, with great care. They must choose the right chatbot to ensure user trust and engagement

Users value two main categories, (1) functionality and (2) feeling, however, what users want from the chatbot also varies depending on the type of task they are seeking help with. "Functionality" is defined in this report as user trust in receiving the right answer and faith in data security processes. "Feeling" is defined in this report by anthropomorphism in design or “humanness”, including empathy and other social factors.

In the tail end of 2024, companies would be wise to clearly segment certain simpler customer service tasks for Basic Chatbots and only attempt to use AI Chatbots for more complex tasks where the quality of output is of a very high standard. As well as provide easy exit points which allow users to contact a human or easily check the information provided to them by a chatbot.

This report contains a literature review of current research and case studies on the topic of chatbots in customer service, as well as the GDPR and other privacy concerns related to chatbot deployment. It looks carefully at how users value chatbot anthropomorphism, chatbot functionality features, and data security and privacy. Subsequently the research methods are set out and then follows a chapter identifying the overall results and findings. The conclusion discusses the results and findings, makes recommendations and concludes the research.

3. Literature Review

As a user there are many obvious benefits to having access to chatbots which include:

immediate responses,

24/7 availability,

personalised interactions,

consistent responses, and

seamless escalation to a human.

Cost savings from increased efficiency may also be passed to the customer. However, it appears that many users are reluctant to engage with chatbots and still have a preference for human customer support. This literature review identified three main features that users consider when choosing whether to engage with a chatbot:

feeling: chatbot design which is user-friendly and enhances engagement through “humanness”,

functionality: delivering accurate and reliable responses, and

privacy: safeguarding data privacy and security.

3.1. Feeling – does chatbot anthropomorphism (“humanness”) increase user engagement or satisfaction?

The term anthropomorphism is used where human-like attributes or characteristics are ascribed to something that is not human, such as a chatbot (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2024; Schuetzler et al., 2024). When referring to anthropomorphism or “humanness” in chatbots, the characteristics discussed are natural and intuitive interactions which mimic human to human communication (Chandra et al., 2022). This is made up of 3 competencies:

Cognitive competency: the ability to process all available information to determine the best outcome.

Relational competency: relationship-building skills that can facilitate engaged communication with others i.e. learning preferences to enable suggestions.

Emotional competency: the ability to moderate its interactions with users, accounting for their moods, feelings, and reactions through appropriate expressions and behavior (Chandra et al., 2022). Ascribing a chatbot a name, avatar and personal story can also create a sense of humanness (Crolic et al., 2021).

Chandra et al. (2022) identified anthropomorphism as an important attribute when designing this type of technology as a means to build trust and connectedness which in turn, leads to higher levels of user engagement, however, it appears that more recent research specifically looking at chatbots illustrates a different view.

Castelo et al. (2023) found that, even when the service provided was identical, service evaluations were more negative when the service provider was a bot, not a human.

The researchers carried out a field study in a coffee shop where they tested customer satisfaction of 109 participants between being served by a robot or a human. Their findings were that this negative reaction to reaction the service provider was a bot was derived from a consumer perception that the organisation had deployed the bot to save money. When the monetary savings were clearly passed on to the customer, the dissatisfaction was counteracted. A central finding was that when bots provide human level service it is viewed less favorably. Therefore, in order to get to a point where it is worth using a bot, technology would have to improve to the point where the bot could provide customer service that was significantly better than a human.

Meyer-Warden et al., (2020) found that empathy did not play a major role in human chatbot interactions characterised by transactional purposes, with users valuing chatbots more for their utilitarian functionality rather than focusing on their social competency.

This came from a study completed in December of 2018, where 146 people who had engaged with a travel chatbot called Flybot were surveyed about their experience. The study analysed how “competence, reliability, responsiveness, empathy and credibility affected the perceived ease of use, usefulness, trust and intention to reuse the chatbot” (Meyer-Warden et al., 2020, p 41).

The study found that in the context it was being applied, “responsiveness, empathy and perceived ease of use did not have any effect on perceived usefulness” (Meyer-Warden et al., 2020, p 41). Therefore, it may be the case that in performing routine, transactional and standardised tasks there is less of a requirement for empathy as long as the chatbot can provide relevant, reliable and functional content.

Crolic et al., (2021) looked at how anthropomorphism impacted users that were in an “angry” emotional state. The research included five studies, including an analysis of a large real-world data set from an international telecommunications company and four experiments.

An important finding was that when users engaged with a chatbot in a state where they were already angry, chatbot anthropomorphism had a negative impact on user satisfaction, overall firm evaluation, and subsequent purchase intentions.

However, this was not the case with users that were not already in an angry state. This negative effect is driven by “expectancy violations” which result from user expectations that an anthropomorphic chatbot will provide a higher level of efficiency and service and when they are unable to, angry customers respond more punitively to their expectations being violated.

This research indicates that expectations created by anthropomorphism in chatbots resulting in higher expectations can be counteracted by reminding the user that they are dealing with an imperfect chatbot and by downplaying chatbot capabilities in situations where users are likely to be in an angry state.

As discussed by Chandra et al. (2022), if possible, the best solution is to meet the high expectations for service to reduce the negative impact of anthropomorphism.

Crolic et al., (2021) addressed some other occasions where anthropomorphism has a negative impact on consumer behavior. For example, anthropomorphic helpers in video games can reduce user satisfaction by undermining the players sense of autonomy, and low-power consumers can view entities such as slot machines as riskier when they are anthropomorphized.

Empathy and generally having a more anthropomorphic style chatbot may be viewed as more important in transactions which involve higher levels of personal service (Meyer-Warden et al., 2020). This may have some application in the future of health services where chatbots may be used in counselling services and other mental health roles, however for the more day to day customer service inquires it is not required (Chandra et al., 2022).

3.2. Functionality – can the chatbot answer user questions reliably?

Arguably the most critical area required for chatbot success, Basic Chatbots are best used for common inquiries with a clear answer. They require little to no personal information and operate as a form of triage system, filtering basic queries from the more complex, collecting the user information required to answer the query, and escalating the more complex questions to a human, either live or as a support ticket. Whereas, AI Chatbots can learn and answer complex questions in the way a human customer support officer would. As a result, they usually require more user data which in turn, needs to be stored and used appropriately.

There is a gap in the current reliability and output between Basic Chatbots and what can be provided by AI Chatbots.

For now, reliability is still the strongest determinant of perceived usefulness and in digital contexts, reliability has the most influence over the users perception of service quality (Meyer-Waarden et al., 2020).

The research cautions against implementing a chatbot without considering the best use, pointing out that Basic Chatbots with pre-programmed scripts may pose a risk of responding to the user’s requests incorrectly or repetitively, leading the customer to frustration (Meyer-Waarden et al., 2020). When implementing a Basic Chatbot, providing customised responses that are tailored and varied increases user engagement (Schuetzler et al., 2020).

While a user is engaging in the question and answer process with a Basic Chatbot to seek an answer to a common questions, there may still be variables. Schuetzler et al. (2020) found that simply providing variety in responses is better than the same questions repeatedly. User satisfaction is raised where follow up questions or responses appear to be tailored, or are at least different (Schuetzler et al., 2020).

A hazard posed by AI Chatbots is the risk of inventing an answer which may put companies at risk in a legal framework that puts the liability on the company which deployed the chatbot. AI Chatbots can produce inaccurate and misleading information which is known as a "hallucination”. Hallucinations are defined as “when a large language model (LLM) perceives patterns or objects that are nonexistent, creating nonsensical or inaccurate outputs” by IBM (IBM, 2024).

In Moffatt v. Air Canada (2024) an Air Canada customer relied on advice provided by an AI Chatbot regarding a bereavement fare refund and purchased tickets only to later discover that the information provided was not correct. When the customer followed the chatbot’s instructions and applied for the refund it was denied by Air Canada. The court ruled that Air Canada was responsible for ensuring the accuracy of information provided by its agent, the chatbot, which had misled the customer and awarded damages. The case highlighted the liability risks of implementing AI Chatbots, particularly those using large language models (LLMs). This certainly should be a consideration when deploying an AI based Chatbot, although employees could also make errors undertaking the same role. More information on this case and the associated risks can be found in "When AI Chatbots Go Wrong: Understanding Liability for AI-Powered Systems"

Developments in AI language processing is rapidly improving and will likely drastically change user sentiment in the coming years, but for now organisations would be wise to carefully consider the two chatbot functionality streams (Basic or AI) and how they suit what they are trying to achieve in their business. As were the findings by Castelo et al., (2023) if organisations choose to implement Basic Chatbots that are not likely to surpass human performance they will likely find this is ill-considered.

At this stage, even being able to match human performance may not be sufficient, more likely Chatbots which unambiguously outperform humans may be required to successfully meet customer expectations when automating a service.

“Thus, the careful selection of clearly defined tasks where bots clearly outperform humans has the greatest potential to realize cost savings without undermining service evaluations” (Castelo et al., 2023)

3.3. Data security and privacy – how does GDPR apply to chatbots?

The general public are becoming more conscious of their privacy and data protection. Coupled with the implementation of the 2016 stricter European privacy regulation, the GDPR (Official Journal of the European Union, 2016), companies are required to be more cautious when implementing new service solutions that collect, store or manage user data.

It gives users a number of rights, however the most relevant to chatbot usage are the right to access, rectify, erase, and restrict processing of the data collected under Articles 12 to 21. These rights impose obligations on organisations to ensure that user data is stored and processed in a way that permits their rights to be actioned.

If the chatbot is able to access the personal data of a user, then the chatbot must have the GDPR mandates in place (Hasal et al., 2021). The definition of “Personal Data” under Article 4(1) of GDPR is extremely broad and covers any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person including a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.

Article 6,1(a) provides that processing of personal data is lawful only if the data subject has given consent to the processing of his or her personal data for one or more specific purposes. Under Article 4(11) ‘Consent’ must be a freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of their wishes, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, which signifies agreement to the processing of their personal data.

Article 7(2) identifies that the request for consent must be clearly distinguishable from the other matters, in an intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language. The data subject shall have the right to withdraw consent at any time and it should be “as easy to withdraw as to give consent”:

Article 7(3). If consent is obtained for performance of a contract / provision of a service, consent is required to collect any personal data that falls outside of the scope of the contract: Article 7(4).

Pursuant to Article 5 of the GDPR organisations need to ensure that consent is sought in the appropriate form and relevant data is:

processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner;

collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes;

adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary;

accurate and kept up to date;

processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security of the personal data; and

kept in a form which permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary.

Each member state has a supervisory body under Chapter VI of GDPR. This public body is responsible for monitoring, enforcing and promoting awareness of the GDPR. Complaints can be raised with those supervisory bodies, which among other administrative outcomes, can result in fines of up to 20 milion euros or 4% of the company’s total worldwide annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher; Article 83(5).

Organisations considering implementing chatbots which will seek “Personal Data” from users, should ensure that they are appropriately seeking consent, only using the data for the purposes consented to, and are appropriately storing the data so that users rights can be enforced under the GDPR, or they may face large fines.

4. Research Methods

4.1. Approach

A mixed method research approach was used which consisted of firstly, a review of the existing literature particularly, on the topics of user trust and anthropomorphism or “humanness” in the design of chatbots. Secondly a survey was undertaken eliciting both quantitative and qualitative feedback, seeking respondent’s personal opinions and experiences using chatbots.

This approach was chosen due to the short duration of the research project. It allowed a sufficient number of responses to be collected and allowed respondents to answer the questions with minimal explanation (Maylor et al., 2017). The survey was circulated to the target population by being posted on the researchers LinkedIn profile, however no natural responses were received. Due to time constraints, the researcher sent the survey to colleagues and friends of the researcher known to be working in the target sectors: education, government, legal and health.

Ethical considerations which were considered included providing a statement of informed consent, ensuring privacy and confidentiality and all information collected from participants will remain confidential, stored securely, that participation is entirely voluntary, ensuring no harm to participants although the risk in this case very low, and the survey was approved before distribution.

4.2. Limitations and potential further research

A major limitation was the small sample size which resulted in all data being considered in the report rather than using the stratified random sampling method which was originally intended. All data was provided in the Appendix of the submission. A number of respondents came from the education sector and the researchers’ place of work, which may have created a bias in the results. All other respondents came from different fields, although they were known to the researcher which raises a question of convenience bias.

Many of the respondents identified as not often using chatbots. In a study of a larger scale, it would be worth looking at what the averages are for chatbot use and aim to get responses from a broad range of respondents. In addition, the survey questions regarding chatbot anthropomorphism, questions 13 – 17, may not be a true representation of how users would act as they may have unconscious biases relating to these features which would be better tested in practical scenarios rather than using a survey.

A further study on this topic could use qualitative methods to look deeper into the survey responses and conduct interviews to better understand users’ perspectives, organisational contexts, and some of the more complex ethical issues related to AI Chatbot implementation.

5. Survey Results and Findings - User Trust & Engagement

All percentages discussed below are rounded to the closest whole number. 36 survey responses were received, with over 60% of respondents coming from the education sector, 22% coming from health, roughly 11% coming from the legal sector and under 4% from government. The primary role of respondents was as administrative staff with almost 40%, secondly respondents fit into the “other” category with roughly 30%. There was also a reasonably strong representation in the roles of healthcare professional and legal professional.

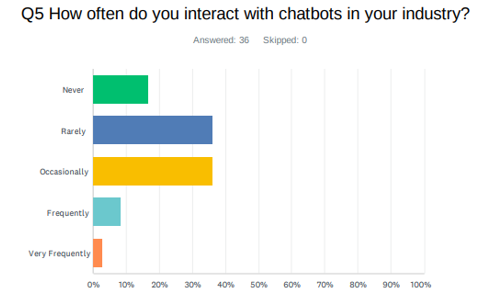

The majority of respondents were between the ages of 35-44 or 45 – 54 years with an intermediate to advanced level of experience using technology. Of the respondents, only 3% interact with chatbots within their industry very frequently, with the majority (36% for both) say they do so Rarely or Occasionally:

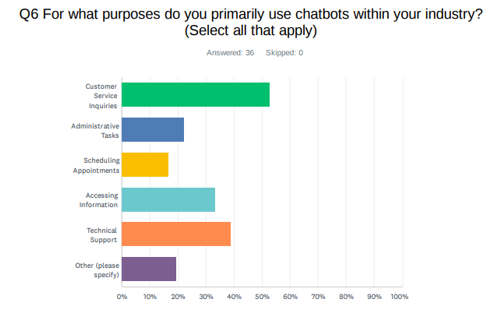

Customer service inquiries (53%) was the most common reason for users to engage with chatbots, with technical support second (39%) and accessing information coming third (33%):

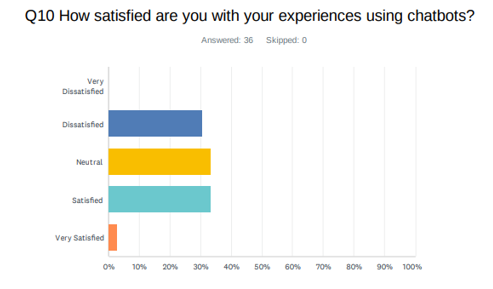

Respondent satisfaction using chatbots was 31% Dissatisfied, 33% Neutral, and 33% Satisfied, only 1 respondent chose Very Satisfied:

5.1. Anthropomorphic Features

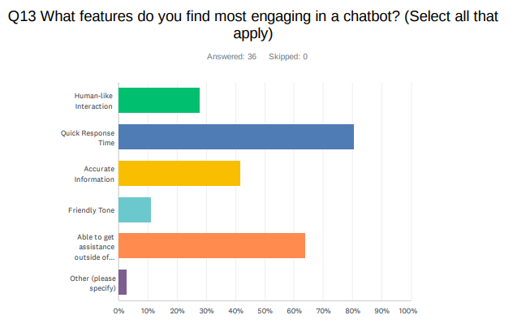

When asked what features they find most engaging in a chatbot, respondents indicated that they clearly value quick response time (81%) and out of hours assistance (64%) highly, as well as accuracy of information (42%). The features most related to anthropomorphism rated lower with 28% of respondents finding human like interaction to be engaging, and only 11% being concerned with the chatbot having a friendly tone:

Users rated their comfort in interacting with a chatbot compared to a human predominantly as Neutral or Less Comfortable (both receiving 39%) and thirdly as Much Less Comfortable (11%):

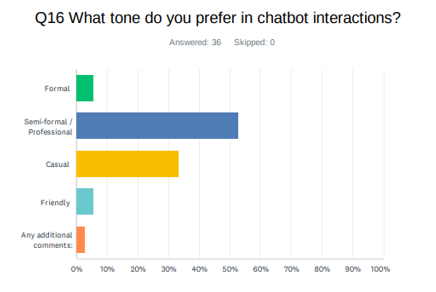

Users identified their preferred tone with chatbot interactions as Semi Formal / Professional (53%) or Casual (33%):

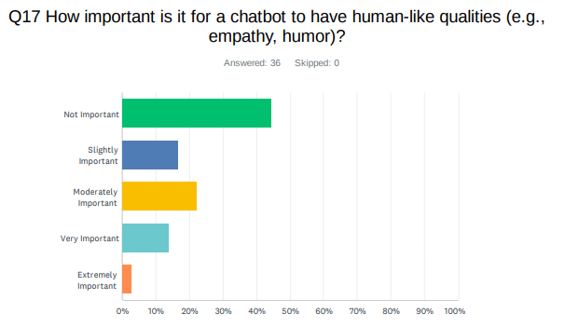

When asked how important it is for a chatbot to have human-like qualities (e.g., empathy, humor), 44% of the respondents felt that it was Not Important with only one respondent saying that it is Extremely Important (3%):

5.1.1 Thematic Analysis

For the related qualitative questions, such as number 23 which asked respondents for their suggestions to make chatbot interactions more engaging and effective, a thematic analysis was used to identify common ideas and response patterns (Ducere Global Business School, 2024). Although the intention of this question was to illicit responses regarding anthropomorphism, many of the respondents provided information that is more relevant to functionality.

Out of 31 responses, 9 had no opinion or the response was unclear. Of the remaining 22 responses, three main themes emerged. The first theme was to improve the chatbots ability to provide an accurate and timely answer to the question. This theme appeared in 11 responses, making up 35% of total responses.

“The technology just needs to improve so that it can understand nuances in language and more quickly to come to the conclusion that it cannot provide assistance with certain inquiries”.

The second theme that emerged was that in cases where the chatbot could not answer the question, the user should be referred to a human customer service representative. This theme appeared in 10 responses, consisting of 32% of the responses.

“It’s best when they know their limits and refer to an actual person promptly. Most of the time if I have bothered going to the extent of contacting support, then the problem I’m trying to fix is complex or I would have already solved it in an online portal somewhere else”.

The third theme related more closely to anthropomorphism, with only three of the respondent’s mentioning friendliness or tone of the chatbot, making up just under 10% of all responses.

5.2. Functionality

Respondents’ knowledge as to whether they were dealing with a Basic Chatbot or an AI chatbot were quite evenly spread from “Never” aware to “Very Frequently” aware. Respondents overall seemed to make very little differentiation between the two types of chatbots throughout the questions and comments.

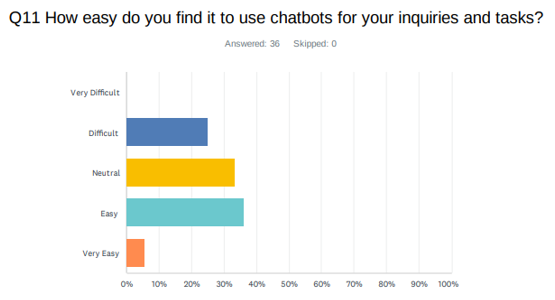

Question 11, "How easy do you find it to use chatbots for your enquiries and tasks?" also highlighted a very mixed viewpoint on ease of use resulting in most responses varying between the central 3 options, Difficult (25%), Neutral (33%) and Easy (36%) with only 6% saying it was Very Easy:

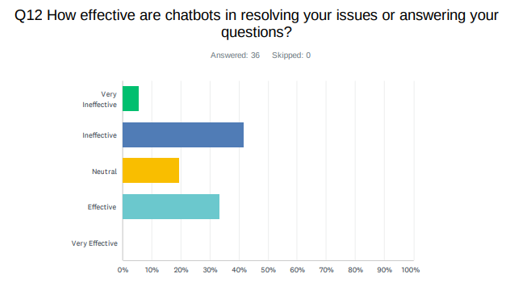

As were users’ feelings towards how effective chatbots are in resolving user issues or answering questions, with 42% finding them Ineffective, 33% finding them to be Effective, 19% finding them to be Neutral and only 6% finding them to be Very Ineffective:

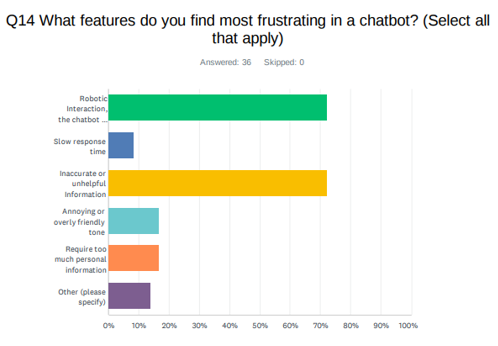

Respondents commonly identified “Robotic Interaction, difficulty understanding what I want”, and “Inaccurate or unhelpful Information” (both with 72%) as the most frustrating issue with chatbot functionality:

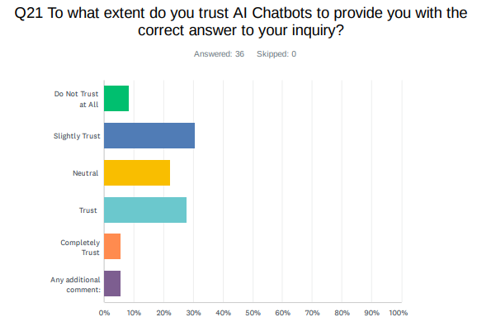

User trust that they will receive the correct answer to their questions was also speckled across a broad range, with more respondents feeling Neutral or having some doubts, than having trust in chatbots:

The qualitative question 24 asked respondents to share a positive or negative experience they have had with a chatbot. Only 3 out of 31 respondents elected not to answer. Out of the remaining 28 respondents, 8 responses were neutral or contained either a partial or fully positive experience where the chatbot completed the required function. The remaining 20 responses shared negative user experiences with chatbots. Two main themes emerged:

inability to provide a reliable answer, with 16 of the responses including some form of this complaint; and

a preference to be referred to a human representative with 4 responses containing this issue.

5.3. Data security and privacy

Respondents were quite diverse in their level of concern regarding the privacy and security of their data when using chatbots, with 14% being Extremely Concerned and on the other end of the spectrum, 22% being Not Concerned. The rest of the respondents fell fairly evenly across the middle range:

Respondents did not express a great deal more concern about the privacy and security of their data when using chatbots as opposed to engaging with a person:

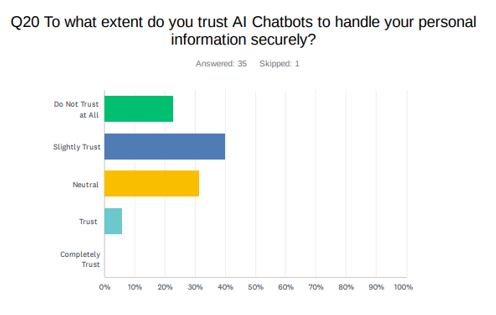

Respondents demonstrated a lower level of trust in an AI Chatbot’s ability to appropriately handle their personal information securely with only 6% of respondents saying they Trust, 31% selecting Neutral and the majority selecting Slightly Trust (40%) or Do Not Trust at All (23%):

In qualitative question 24 asking about negative user experiences, discussed under the previous heading, two responses that were grouped in the “Other” category were concerns relating to users being required to disclose too much, or unnecessary personal data:

“Don't like the types that no matter what question you ask, it prompts you for your email address to continue any engagement.”

“I avoid them where I can. A person is always faster and more efficient. I think chatbots reflect poorly on companies that use them and are often a datagrab...”

6. Discussion, Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Discussion

In 2024, chatbot and other AI technology is developing at such a rapid pace that we are on the edge of a new technological breakthrough, whereby chatbots will most likely very soon be able to simulate authentic empathy and win over the trust of users.

We are not quite there yet, and this is reflected in user sentiment in both the literature and the survey results from this research. Users still hold AI Chatbots to a higher standard than a human customer service agent where the chatbot demonstrates human like qualities. This can be counteracted by informing users that any cost savings are passed on to them, being transparent about the limitations of the chatbot, and ensuring that there are exit points from the chatbot which connect users with human agents.

With AI Chatbots potentially completing functions in the future such as counselling or medical interviews, it may be that more trust is needed therefore chatbots will need to be more anthropomorphic to gain user trust.

AI technology is just on the brink of where service (both functionality and feeling) provided by chatbots could exceed that of humans which could potentially counteract any dissatisfaction bias experienced. However, this new phase of technology brings with it new challenges such as AI “hallucinations” and new privacy threats.

AI Chatbots will require much more robust security features. Yang et al., (2023) have suggested requiring a login to engage with an AI Chatbot, as well as the following “best practice“ security steps for implementing chatbots:

Conduct comprehensive security assessments.

Implement user authentication and authorization.

Use encryption for data protection.

Regularly update and patch chatbots.

Educate users on security best practices.

The research supports the view that Basic Chatbots do not need to be anthropomorphic if deployed effectively on repetitive and simple tasks that have clear answers.

This is because users do not generally provide a lot of personal information and therefore, do not need to trust them. Basic Chatbots deployed in more complex situations where they are not capable and frustrate the user can cause irreparable damage to user satisfaction and loyalty. For these reasons, organisations would be wise to carefully consider the different use cases to determine which chatbot type is better in each role.

6.2. Conclusion and Recommendations for Choosing the Right Chatbot

Although chatbots are largely deployed in customer service roles, the research seems to indicate they are operating at an underwhelming capacity with many users reluctant to engage with them. There needs to be more clarity around where chatbots are useful and effective and organisations should avoid using them simply as another member of the customer service team. Not all companies will be able to afford AI Chatbots, and the Basic Chatbots are cheap and effective if deployed correctly for basic tasks. Many CRM platforms, such as HubSpot, are offering effective chatbot builder software in their platforms to help organisations automate customer interactions, enhance lead generation, and streamline support while maintaining data security and compliance.

If organisations do choose to look at deploying either a Basic or AI Chatbot, they need to be very clear on what exactly is its purpose, and whether it will be able to effectively manage that purpose, all while meeting user expectations for both function and feeling.

Having two distinct streams of chatbot design also assists to potentially avoid engaging the data collection and privacy requirements under the GDPR. In many customer service scenarios, organisations could avoid collecting user data unless it is completely necessary, as once they have done so, they may find themselves having to ensure collection, storage and disposal under the GDPR and put themselves at risk of high fines if they do not comply. This also benefits users, many of whom are not inclined to provide additional personal data to a chatbot.

About the Author

I am a business process improvement specialist, AI consultant, and lawyer with extensive experience in EdTech, government, and mining. My background in process automation, AI deployment, and regulatory compliance has allowed me to work across high-privacy sectors, including courts, tribunals, higher education, and government agencies.

I focus on helping organisations streamline operations, enhance customer and student engagement, and implement AI-driven solutions to improve efficiency and compliance. With expertise in workflow optimisation and automation, I bring a unique blend of technical and legal insights to ensure businesses can leverage emerging technologies while meeting strict regulatory requirements.

Looking to Optimise Your Business with AI & Automation? Let's Talk

If you're looking to streamline operations, integrate AI solutions, or improve customer and student engagement, I can help. With experience in process improvement, automation, and AI implementation, I assist businesses in EdTech, government, and mining in making their workflows faster, more efficient, and regulation-compliant.

📅 Book a free 15 minute consultation to discuss how we can optimise your processes and enhance your business performance. 👉Reach out through my website here.

7. References

American Banker. (2022, 6 6). Chatbots: the entry point into larger digital banking transformation. American Banker, pp. 3-3.

Castelo, N., Boegershausen, J., Hildebrand, C., & Henkel, A. P. (2023). Understanding and Improving Consumer Reactions to Service Bots. Journal of Consumer Research, 50(4), 848-863.

CBInsights. (2021, 1 14). CBInsights. Retrieved from Research Report - Lessons From The Failed Chatbot Revolution — And 7 Industries Where The Tech Is Making A Comeback: https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/most-successful-chatbots/

Chandra, S., Shirish, A., & Srivastava, S. C. (2022). To Be or Not to Be ...Human? Theorizing the Role of Human-Like Competencies in Conversational Artificial Intelligence Agents. Journal of Management Information Sytems, 39(4), 969-1005.

Conger, M. (2016, 8). Welcoming our Chatbot Overlords: Why the world needs to look to China, not the US, for innovation in this sector. China Business Review, N/A(N/A), 1-1.

Copeland, B. J. (2024, 5 17). Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved from Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/technology/artificial-intelligence

Crolic, C., Thomas, F., Hadi, R., & Stephen, A. T. (2021). Blame the Bot: Anthropomorphism and Anger in Customer–Chatbot Interactions. Journal of Marketing, 86(1), 132 - 149.

Dhanya, C., & Ramya, K. (2023, July). Customer Perception of Chatbots in Banking: A Study on Technology Acceptance. IUP Journal of Management Research, 22(3), 22 - 39

Ducere Global Business School, CDP706 Career Applied Project, 3.4. Sampling & Analysing Data.

Echt-Wilson, A. (2021, 8 13). How HubSpot Personalized Our Chatbots to Improve The Customer Experience and Support Our Sales Team. Retrieved from HubSpot: https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/chatbots-improve-customer-experience-experiment

Fatani, M., & Banjar, H. (2024). Web-based Expert Bots System in Identifying Complementary Personality Traits and Recommending Optimal Team Composition. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (IJACSA), 15(2), 106 - 120. Retrieved 5 18, 2024

GDPR.EU. (2024). What is GDPR, the EU’s new data protection law? Retrieved 0623 2024, from GDPR.EU: https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/

Hann, K. (2024, 04). How Businesses Are Using Artificial Intelligence In 2024. Retrieved from Forbes Advisor: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/software/ai-in-business/

Hasal, M. N., Saghair, K. A., Abdulla, H., Snášel, V., & Ogiela, L. (2021). Chatbots: Security, privacy, data protection, and social aspects. Currency and Computation Practice and Experience. Retrieved 06 11, 2024, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cpe.6426

IBM. (2024). What are AI hallucinations? Retrieved 5 19, 2024, from https://www.ibm.com/topics/ai-hallucinations#:~:text=AI%20hallucinations%20are%20when%20a%20large%20language%20model,that%20are%20nonexistent%2C%20creating%20nonsensical%20or%20inaccurate%20outputs.

IBM. (2024, 5 18). What is a chatbot? Retrieved from IBM: https://www.ibm.com/topics/chatbots#:~:text=A%20chatbot%20is%20a%20computer%20program%20that%20simulates,understand%20user%20questions%20and%20automate%20responses%20to%20them.

Lappeman, J., Marlie, S., Johnson, T., & Poggenpoel, S. (2023). Trust and digital privacy willingness to disclose personal information to banking chatbot services. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 28(2), 337-357.

Martinez, R. (2018). The Power of Artificial Intelligence: Applying new technologies such as chatbots and A.I. to your global operations. Franchising World, 50(5), 92-94.

Maylor, H., Blackmon, K., & Huemann, M. (2017). Researching Business Management (Vol. 2nd Edition). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Merriam-Webster Disctionary. (2024). Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 08 4, 2024, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/anthropomorphic

Meyer-Waarden, L., Pavone, G., Poocharoentou, T., Prayatsup, P., Ratinaud, M., Tison, A., & Torné, S. (2020). How Service Quality Influences Customer Acceptance and Usage of Chatbots? Journal of Service Management Research (SMR), 4, 35-51.

Moffatt v Air Canada (2024), https://www.canlii.org/en/bc/bccrt/doc/2024/2024bccrt149/2024bccrt149.html

Official Journal of the European Union. (2016, 4 27). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Da. Retrieved 06 28, 2024, from EUR-Lex Access to European Union Law: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

Pasquarelli, A., & Wohl, J. (2017, 7 17). Betting on Bots. Advertising Age, 88(14), 0014-0014.

Perry, P. M. (2024, 1). AI INFILTRATION: Businesses are learning how to balance the benefits of AI with the potential risks. LP/Gas Trade Publication, 84(1), 38-43.

Sarvady, G. (2017, 12). Chatbots, Robo Advisers, & AI: Technologies presage an enhanced member experience, improved sales, and lower costs. Credit Union Magazine, pp. 18-22.

Schuetzler, R. M., Grimes, G. M., & Scott Giboney, J. (2020). The impact of chatbot conversational skill on engagement and perceived humanness. Journal of Management Information Systems, 37(3), 875-900.

Yang, J., Chen, Y.-L., Por, L. Y., & Ku, C. S. (2023). A Systematic Literature Review of Information Security in Chatbots. Applied Sciences, 13(11), 6355.

Comentários